Reflections on Mac

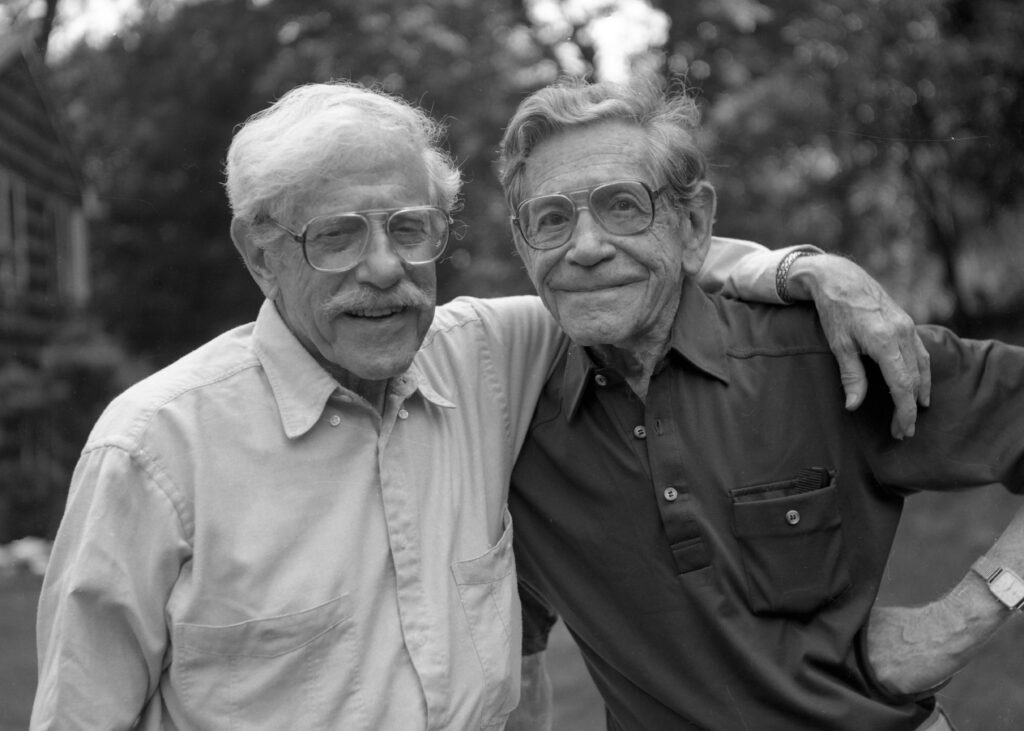

I knew Mac as his nephew. I was raised by my parents but grew up with Mac because my father and uncle always shared a home, first their parents’, then the house they bought together. It was a one-family house converted to two with the addition of stairs just inside the front door. The original stairs in the middle of the house survived but no longer served as a passageway so much as a social space. Adjacent to the landings were my uncle’s and father’s studios, Mac’s upstairs, my father’s below. At the top and bottom of these stairs were old-time light switches that clacked loudly when you’d flip them on or off, so whenever my father wanted to talk with my uncle, or my uncle to my father, they’d toggle the light switch up and down, up and down, several times, clackety-clackety clack. If the other brother didn’t hear it, the light would be left on as a signal so that whenever he passed by and noticed, he’d come to the stairs and clackety-clack the switch until the first reappeared. That’s how they called to speak to each other several times a day, my father sitting on the bottom steps looking up through the slats, my uncle at the top looking down.

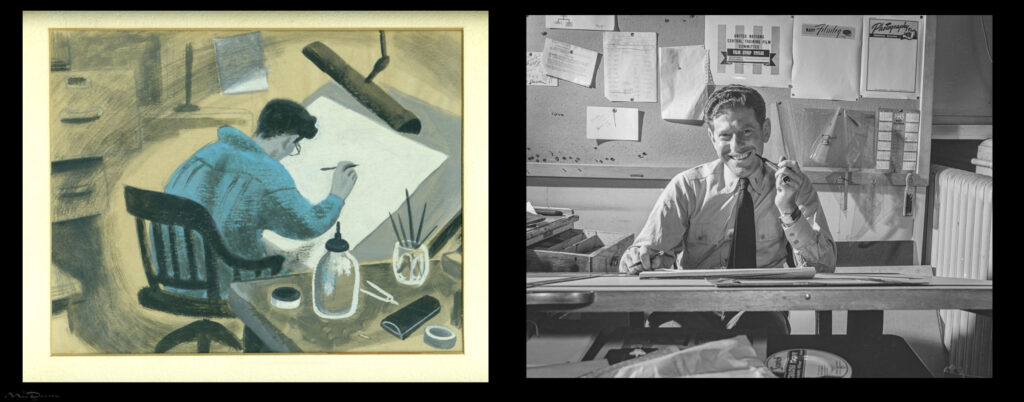

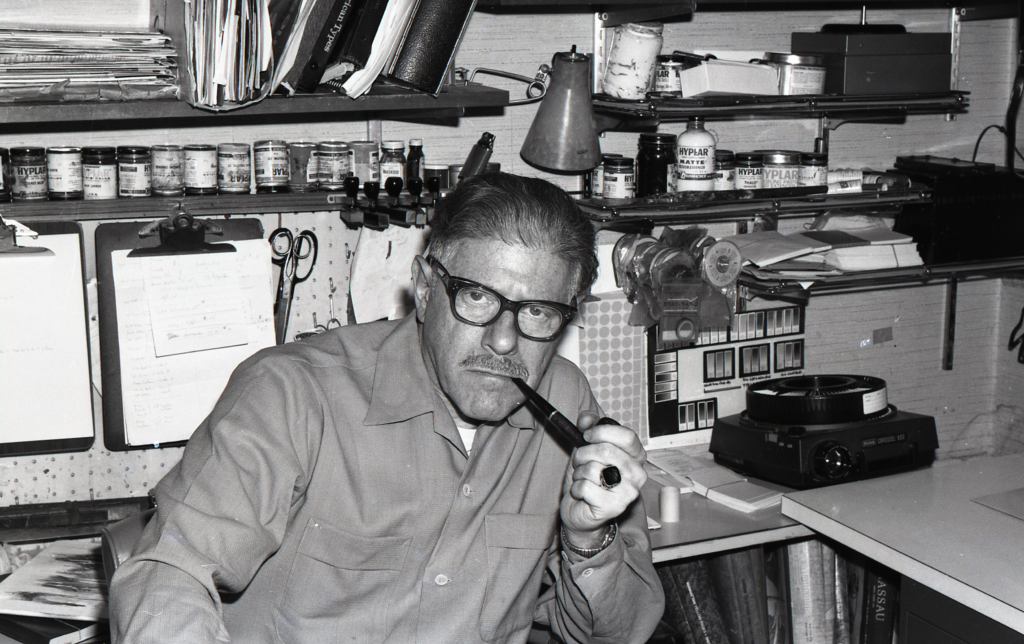

Their studios were conceived before I was. Reason and old photographs agree that the rooms began tidy and trim, but by the time I could clamber up stairs their workspaces were shaped by organically-tailored accretions. Some of their furniture had apparently been broken before the point of accession, probably excessed from their parents’ house or salvaged from somewhere because somehow it fit the space and satisfied a purpose. Everything they needed would have been reachable within the rolling distance of their chairs if so much else hadn’t been in the way. This agglomeration made the spaces cozy and comforting. So did the air. I would have known Mac’s studio blindly from the imbued perfume of acrylic paints, rubber cement, and flavored pipe tobacco — and also, increasingly, by the subtle scent of a heated slide in his paint-spattered Kodak Carousel, from which he projected his photographs onto white cardboard hung from a file cabinet. Those photos were not art but snapshots, a way to bring complex outdoor visuals back into his eyes so he could paint indoors. Only in his youth did he stand an easel outdoors, a practice he seems to have abandoned after a pair of eager untended dogs lapped his watercolor bucket dry, and that just minutes before a train bore down on him. He did finish his painting of the Grand Hotel station, but apparently after that he retreated to work in the comfort (and safety) of his studio.

If family lore warrants belief — and it almost certainly does not, but the story might be telling — my grandparents fretted that an artist’s earnings could not sustain the family but that my father’s income as an interior designer could, so they ruled that Mac would serve in WWII and my father could claim an exemption as the family’s sole support. Whether by arrangement or fate (most likely fate, since my father had aged out of the draft by then), that’s how it turned out. It’s not quite true, then, what I said, that the brothers lived the whole of their imbricated lives together: Mac spent World War II in DC in the Navy, recruited as an art director alongside Walt Disney’s artists in the Training Film and Motion Picture Branch, ultimately as a lieutenant, junior grade. Even if he would have resented his parents’ supposed edict, the Navy supplied him with great times and excellent training.

Mac’s formal training was in commercial art, with a degree from Cooper Union and courses at Pratt, American University, and NYU, all at night so he could work in the day. By the time he was, without his knowledge, recommended to Navy recruiters by Dun & Bradstreet, his clients included Collier’s, American Magazine. Country Life, McCall’s, United Press, WNEW and WMCA radio stations, and a host of advertising agencies. But the Navy fostered his mastery of filmstrips. For those of us old enough, filmstrips were torturously boring static projections on dingy screens in front of the classroom. But the continuous crawling loops that Mac produced were different: substantial yet playful, joyous, colorful, and amusing – not exactly what one might expect in an ad for a company specializing in market analytics.

We could well imagine today those same graphics edited digitally into a flashy product, yet the fundamental artistic craft would be unchanged: It would be the same art, only with the camera pushing, tilting, tracking, panning, racking and blurring, flashing and spinning, but basically the same design, plus a soundtrack.

Mac won, by my count, seventeen medals for his filmstrips, five of them gold, but he stopped listing filmstrips on his credits once his watercolors began collecting awards. Unquestionably, filmstrips had become passé and were understood to be a lesser art form (if art at all), but Mac didn’t lose pride in them and never removed “filmstrip producer” from his Who’s Who entries, although it did come third after “artist” and “art director.”

It was Mary, his wife, who spurred Mac to paint seriously. He was well into middle age by then and no doubt bore the seed but needed fire to break the dormancy. He studied formally under only one artist, Barse Miller, first at Queens College and later at Rangemark in Maine. Everything else he learned on his own. Miller’s influence is not glaring though might be inferred from some of Mac’s earliest art, but Mac rapidly evolved into his own form that seems to have inherited nothing from Miller.

Among Mac’s early impulses were piers and harbors. He was not a boater, and to my knowledge never set foot on a ship in the Navy. He didn’t fish. But in the mid-1970s, he and Mary bought a summer cottage in Montauk, where he would go to the commercial docks to photograph the boats and rigging. It was the visual beauty and congeries of lines and syncopated rhythms that attracted him, not any spiritual ties to the sea or romanticizing of the deck hands. Gregarious as he was, I never heard of him conversing with the fishing crews. They probably saw him and had no interest. Montauk is like that.

Mac and Mary at first knew no one in Montauk but loved the setting and the vibe. Their cottage was a modest kit house that fit them like an old easy chair about which you would not boast and yet was inordinately comfortable to them. Their sphere quickly filled with everyone from up and down the street, all of whom together formed a company of friends, each apparently with enough furniture to bring the rest of the crowd into one room at one time. The only ones I knew by more than name were Ed and Betty Persan, the closest both geographically and socially, who built a house next door on an empty acre that Mac and Mary could have bought but, providentially, didn’t. One of Ed’s sons recounted their relationship, told here by the author Tom Matthews:

The house next door was owned by Maxwell Desser, a painter of seascapes and boats, big in the American Watercolor Society, not so good around tools. Ed took care of him. “Max was a painter, so he didn’t know much. My father would always be over there doing his work. You’d hear him yell, ‘Don’t worry, Max. Come on, Bobby, we’re gonna rip out Max’s fascia and put in a new one.’” Desser reciprocated with paintings. Ed’s favorite was a large picture of Nick’s Fishing Station in Shinnecock. “Big bunch of boats sticking out,” Bob said. “Kind of abstract – but nice.” His father liked the picture so much, he started taking it with him to Florida for the winter. When Desser found out, he painted a copy, exact except for one detail: He changed the boat trim from wood to chromium to make it look better in Florida waters.” —Our Father’s War, Tom Matthews

Bobby might be right about Mac and handicraft. Mac was an artist but not an artisan. He attended to every brushstroke and hue, but his interest in craft seemed to end there. He didn’t care a blink about anything beyond the inner boundary of the mat. He certainly didn’t care about the frame. At exhibitions, every artist but Mac would perfectly fit their work into a handsome frame, clean and often pricey. Mac’s frames were often acquired workhorses, the brethren of shipping crates, dinged, scraped, and smudged. Having learned his craft mostly on his own, he knew none of the rudiments of framing. He used such an excess of hanging wire that sometimes you had to strip some back to get the frame onto the wall hooks. More critically, instead of proper hinging tape, he used gummed shipping tape to fix his paintings to mats. That tape will either never come off or will crumble with time leaving a stain at the perimeter of the paper, fortunately well beyond the boundaries of the painting itself.

At the household in Queens, my mother was the first to die, then Mary, and then my father, and so Mac suddenly lived alone in a house once bustling with four adults, a kid, a smart but surly cat, and an adoring dog. He outlived most of his friends, and would go to Montauk only for the day and only with me, more to check on the house than to actually be there. A year later a fall on a broken sidewalk badly injured an eye. His stoicism, or reserve, hid much that I should have seen. He kept painting, though, and rushed to complete one in time to enter it into what would be his last exhibition. By the deadline, he hadn’t felt the painting was ready, though it captured an award.

After Mac died and the time came to sell the Queens house, I went to the attic where much of his art lived, and began sorting through hundreds of paintings, dozens of them unfinished. Among my first missions was to find their names. I worked from exhibition catalogs, books, magazines, websites, collection listings, and any newspapers that had pictures of his work so that I might find the titles, but mostly I had a thousand slides he took of his art which sometimes, though not often enough, he would label. Surety eluded. Sometimes there were variations in names from one source to another; other times there seemed to be two rather different paintings with the same name. One name that especially threw me, because it seemed assigned to several paintings in his Harbor Patterns series, was “Topside.” Only when I found a painting in the Music Series also named “Topside” did I realize that he had just grown weary of his paintings being shown upside down and so labeled the top edge of the photographs “top side.”

These photographs that wrought confusion were also revelatory. They were often the only record of paintings that had been sold — many more than I’d realized — but moreover they revealed how considerably Mac sometimes revised his work. Even a signature on a painting was no assurance against further alteration, often extensive. Sometimes I thought I was looking at duplicate slides only to realize that while the core elements were the same in both images, all the substratum, ambience, and dressing had changed. Two photos of “Music Series, Seriatim #54”, for instance — that is, the painting unintentionally published upside-down in a textbook — looked the same at first blush and showed Mac’s signature in the same place, yet a thousand details varied between versions (which differed, too, from the finished painting):

I had other slides I thought were of entirely different paintings, but eventually realized that one was a rebirth of the other. Slides of a painting of the Montauk lighthouse seen from below the bluffs, for instance, I at first believed were two distinct paintings, but they seem in fact to be the same painting in two stages of revision:

Mac never stopped perfecting, and never stopped evolving. Although I described his style as “singular” since it’s distinct and recognizable, it was never static or formulaic. Age, rather than ossifying him, sustained his confidence that if he kept at it, he could do yet better. The struggle he described — the extensive editing, altering, reexamining, and revising — was part of the art, and part of being an artist. If he had another hundred years, I’m sure that the unfinished work in the attic would have been finished, but still as many unfinished pieces would have taken their place.

Stuart Desser

An aim of this website is to catalog all of Maxwell Desser’s paintings, including many of which I have photographs but not possession, as well as those for which I have not even a photograph. From the Web it appears that only a tiny number of his paintings have been resold at auction, and those are almost exclusively small paintings that he gave to the Salmagundi Club for its thumb box sales. I would appreciate hearing from any owners of Desser’s paintings, especially of art not pictured here, and to receive name corrections and any comments.

Contact:

____________________________

Credits and Attributions:

● The drawing of Lieutenant Desser is assuredly by one of his colleagues in the Navy, but the work bears no signature.

● Our Father’s War is by Tom Matthews (Broadway Books, 2005).

MEMBERSHIPS:

● American Watercolor Society, https://americanwatercolorsociety.org/

Dolphin Fellow.

● National Academy of Design, https://nationalacademy.org/

National Academician.

● Audubon Artists, https://audubonartists.org/

● Allied Artists of America, https://www.alliedartistsofamerica.org/

● National Society of Painters in Casein and Acrylic,

https://www.nationalsocietyofpaintersincaseinandacrylic.com/

● [additional entries to come]

GALLERIES: